A famous tale commonly used to describe a colossal failure in setting your priorities right refers to the Byzantium elites of the mid-15thcentury, fiercely arguing over the “gender of angels” according to sacred texts, while Constantinople was under siege by the Turks.

I thought about the Byzantium intellectuals as the 2018 FIFA World Cup semifinalists were greeted with some degree of surprise by football media in many countries, especially those countries that did not live up to expectations or, -worse- those that could not even qualify to arguably the most exciting sports event in the world.

Of course, it is easy to explain what happened in hindsight; however, I believe that an often-overlooked perspective in international football is the relationship between key regulatory decisions and sportive success. Moreover, the 2018 FIFA World Cup provided very compelling evidence that some regulators, i.e. national football associations, can no longer ignore a fundamental axiom in global football:

“There’s a direct relationship, a positive correlation, between the level of openness and integration of a nation’s football and international success.”

Let us try to explore what “openness” and “integration with the rest of the world” entail, or how “openness” can be measured. Drawing an analogy to the openness of a macroeconomic system (national economy) of a country, I argue that we can employ six factors to gauge the level of openness of a nation’s football:

- Number of foreign players in the league

- Number of players in other leagues

- Number of foreign coaches in the league

- Number of club-grown players in the league

- Concentration of power in domestic leagues

- Number of clubs owned privately/foreign investors in the league

Let us now discuss how the semifinalists in the 2018 FIFA World Cup (England, Croatia, France and Belgium) compared with less-successful nations according to their level of openness in football. I have compared these metrics specifically with figures from three other UEFA nations, namely Italy, the Netherlands and Turkey, since these countries rank within the top 15 in terms of their football markets and, especially in the case of Italy and the Netherlands, are considered as regular participants in the World Cup.

- Foreign Players in the League

With the exception of Croatia, it can be argued that nations that have a higher percentage of foreign players in the domestic top-tier league have had higher levels of success internationally.

England: 68,1%

Belgium: 63,1%

France: 46,6%

Croatia: 38,5%

As a matter of fact, with the exception of Serbia, Iceland, Sweden, Poland, Denmark there is not a single European nation that qualified for the World Cup with a ratio lower than 40% of foreign players in the domestic league. Among these, only Sweden (30,1%) and Denmark (37,3%) advanced from the group stage.

In our comparison group, the ratio of foreign players in the domestic league are presented below.

Italy 55,8%

Turkey 48,2%

Netherlands 36,6%

- Players in Other Countries

Having foreign players in the domestic league is of course not enough by itself to serve as a measure to understand how open a country is in terms of football. Just as we should also check the exports of an economy in addition to imports, we need to look into how many players a country has playing professional football in other countries:

France: ranks #2 in the world with 781 French players active around the world

England: ranks #4 with 451 players

Croatia: ranks #8 with 323 players

Belgium: ranks #15 with 216 players

I think that the conclusion is clear from this perspective. The more players a nation has outside as expats, the more likely it is to succeed internationally. Let us check our comparison group of 3 nations:

Comparison group:

Netherlands – ranks #13

Italy – ranks #26

Turkey – not in top 50

It is quite interesting to interpret the number of foreign players in the domestic league and the number of players in other leagues in combination. For instance, if you consider France, the World Cup winner, who is on top in terms of both metrics, it unquestionably shows that the French football landscape is extremely vibrant, manifested in both attracting outside talent and producing talent to be attracted in other markets.

- Number of Foreign Coaches in the Top-tier League

Openness of a country’s football cannot only be measured by foreign players. Qualitatively, it can also be argued that foreign coaches in the league is even a more significant indicator in this respect. Let us see how the 2018 FIFA World Cup semifinalists fared:

Croatia: 2 foreign coaches in 10 clubs in the top-tier league

Belgium: 4 foreign coaches in 16 clubs

England: 14 foreign coaches in 20 clubs

France: 5 foreign coaches in 20 clubs

Comparison group:

The Netherlands: 2 foreign coaches in 18 clubs

Turkey: 2 foreign coaches in 18 clubs

Italy: 1 foreign coach in 20 clubs

Other major European leagues have a similar pattern. Bundesliga has 3 foreign coaches in 18 clubs. La Liga has 3 foreign coaches in 20 clubs. These figures suggest that, countries with higher level of success in the 2018 FIFA World Cup tend to have a slightly higher number of foreign coaches in domestic leagues.

- Number of Club-trained Players in the League (2009-17 average)

A “club-trained player” is a footballer who has spent at least three years between the ages of 15 and 21 in their team of employment. One of the most common arguments in football, which is almost never argued against, is that club-trained players are good for national football. Facts do not confirm this argument, however.

The reason is simple: a lower ratio of club-trained players indicates a more active transfer market in a league, and conversely, a high ratio would mean a less dynamic transfer market in the league.

I believe that a high ratio can also be interpreted as a football market where the distinctions between “feeder clubs” and “competitive clubs” are stricter, and points to a structure where the best talents inevitably end up in the few powerful clubs at an early age.

Let us compare this metric in the 2018 FIFA World Cup quarterfinalists, and the comparison group:

Croatia ranks #2 in the UEFA zone with 32,5% of players in the top-tier league are club-trained

Belgium ranks #24 with 14.5%

England ranks #25 with 14,1%

France ranks #16 with 23.2%

Comparison group:

Netherlands – ranks #17 with 22,9%

Italy – ranks #30 with 9,1%

Turkey – ranks #31 with 8,8% (lowest in the UEFA group)

An extension of this factor would be the “% of club-trained players in the national championship winner teams” during the same 10-year period.

Croatia ranks #11 in the UEFA zone with 27,9%

France ranks #16 with 23.2%

Belgium ranks #19 with 20,8%

England ranks #20 with 19,8%

Among the comparison group, figures are more interesting:

The Netherlands rank #1 with 40,8% of club-trained players among national league champions.

Turkey ranks #27 with 14,5%

Italy ranks #28 with 12,4%.

Moreover, there are several academic studies[1]that research the correlation between the percentage of club-trained players and sportive success (measured by the UEFA ranking), which show that no such correlation exists.

This argument in reverse form would be that the more active the transfer activity in the national league, or the less concentrated the top talents of the country in a few clubs, the more likely for a country to succeed internationally.

- Concentration of Power in Domestic League

I believe it is not necessary to elaborate that higher competition leads to more efficient markets, as this is a well-established argument in economic theory. While higher domestic competition does not necessarily imply openness in international economics and trade, such an argument can definitely be made in football, especially in the case of the UEFA area.

In other words, it can be argued that a domestic league with a more even competitive field in football can be considered as a more open system than a league with less even competition. In plain terms, this can be interpreted as the income distribution in an economy, which measures how much wealth is concentrated in the hands of the rich vs the middle class.

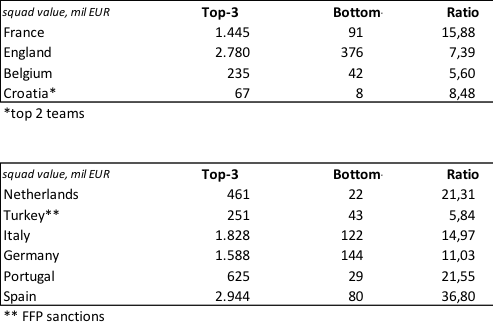

I measured this metric by comparing the market value of the top 3 teams in each domestic league compared to the average value of the bottom 3 teams.

Now let us check the competitiveness metric of the World Cup semifinalists and our control group:

These figures indicate clearly that the UEFA countries with a more even competitive field performed way better in the 2018 FIFA World Cup compared to countries in which squad values are more concentrated.

6. Foreign / Private ownership

Of course, one very important metric that can be regarded as an indicator of openness of a nation’s football market would be private/foreign ownership of football clubs. This is a very heated discussion topic and during the last years we see more general trends of a greater acceptance of private ownership of football clubs. While jury is still out about the cultural aspect of this discussion, I believe that the discussion should concentrate on accountability (read: skin in the game) rather than ownership. Simple logic dictates that in the long run, privately owned football clubs will be better governed than structures where short-termism dominates since it is not clear who pays the financial or non-financial consequences of bad management[2].

From this perspective, the semifinalists in the 2018 FIFA World Cup were clearly progressive:

In Croatia, Prva HNL, the highest league, has 10 football clubs; and at least 4 are owned privately, few by foreign investors.

In the Belgian Jupiler Pro League, out of the 16 clubs, 11 are owned privately, and very interestingly, a few by other clubs or owners of other clubs in the UEFA area.

France (Ligue 1) and England (Premier League) do not even need to be discussed as private and/or foreign ownership is overwhelmingly common.

Natural conclusion from the above is that private ownership of clubs clearly benefits the nation’s football internationally. When we look at our comparison group, as well as several other countries in the UEFA region, the argument is further strengthened.

Conclusion:

In this article, by using six criteria to compare the level of openness of a nation’s football and recent results from the 2018 FIFA World Cup, I argue that:

- the more open a nation’s football industry is, the more likely it is for that country to succeed internationally, and

- arguments/policies in favor of protectionism in football in each of the five policy areas are baseless.

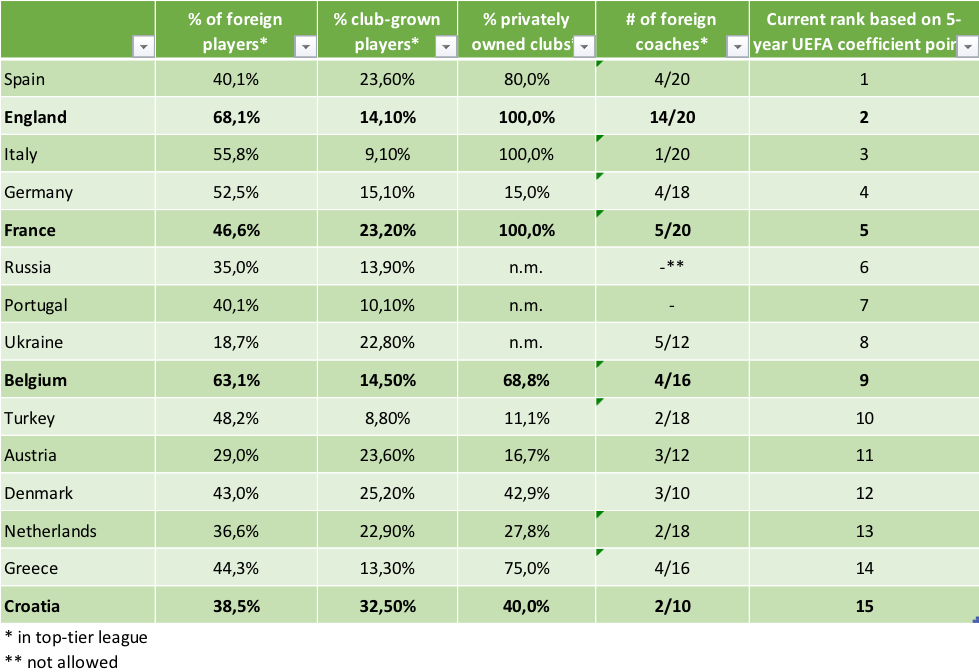

As a sanity check, I also include four of these criteria for the top-15 UEFA countries based on the current ranking in the following table, which I believe strengthens the central argument above.

Finally, I also argue that in the coming years, the divide between open and unopen football nations will continue to grow; and countries with more open regimes will expand their dominance over protective regimes, both in club and national level.

Isitan Gün is Professor in Financial Strategy of The FBA’s Professional Master in Football Business and Chairman at Dutch Eredivisie club Fortuna Sittard. He can be contacted via LinkedIn.

[1]Drs. Raffaele Poli, Roger Besson and Loïc Ravenel, The CIES Football Observatory 2017/18 season, June 2018

[2]Disclosure: I am the majority shareholder of the Eredivisie club Fortuna Sittard in the Netherlands.